The only sign of human activity was the four pairs of chef clogs resting on a mostly empty shoe rack.

I briefly panicked, wondering if I’d already committed a faux pas by not removing my boots. I hesitantly ventured up to the third floor meeting room, where a quick floor scan reassured me that I was not alone in keeping my shoes on.

A quick sigh of relief, then I was welcomed with several broad, reassuring smiles.

So this was the Islamic Council of Victoria (ICV), where even budding journalists are greeted with a warmth rarely evident in all but the smallest government departments.

They had a good reason to be so welcoming, as explained by Cameron Thomas, the ICV’s Campaigns and Media Co-ordinator, a man with sharp eyes and a firm grasp of the problems that Islam has come up against in Western attitudes.

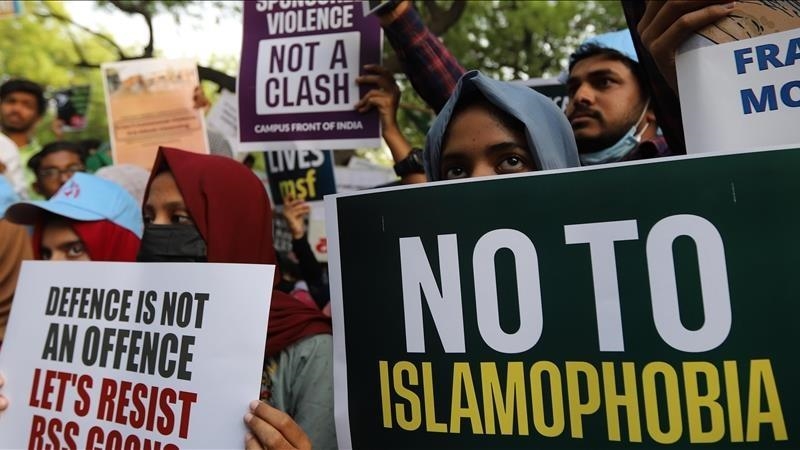

‘We need to be more proactive, both of us,’ Mr Thomas said about efforts to alleviate Islamophobia.

‘Muslims need to be more proactive in communicating the key messages of Islam, and non-Muslims need to be more proactive in trying to understand the key messages of Islam.’

The trouble is that we need to want to be more proactive, if we are to peaceably live together.

But for Mr Thomas, ‘there’s a perception that the benchmark of a political and dutiful citizen is to follow current affairs, and really nothing else… if something is blatantly contentious we should investigate it.’

The newly appointed media liaison for the ICV isn’t exactly bandying words, having previously worked for the Daily Sabah as an editor and writer. ‘We’re dealing with a culture where we consume information passively and not actively,’ Mr Thomas said.

It’s a form of ‘ignorance’ he said, but ‘we’re all ignorant of a lot of things.’

For the ICV, it’s a matter of convincing the non-Muslim community that this is one area of ignorance that needs to be addressed. They’re fighting a losing battle at the moment, and they know it too well.

Maryum Chaudhry, a Youth Engagement Officer at the ICV, said there was an issue of language.

‘It’s very much reflected through government policies and commentary and that impacts us directly,’ she said.

‘The words that are used have influence on people’s minds and perceptions and stereotypes, there’s a direct impact in the rise of Islamophobia and institutional racism.’ Mr Thomas referred to the wildly divergent ways terrorism is framed in the media.

We see a young white American go on a college shooting spree and it fits into a mental health narrative, but we see a Muslim do something similar, and immediately it’s a matter of, ‘We don’t know all the facts but we know it’s terrorism.’

Ms Chaudhry said ‘it becomes difficult to engage in certain [media] conversations, or change the conversation to what really matters when the narrative’s already been scripted for us.’

Ms Chaudhry highlighted one issue that has made engagement between Muslims and the media problematic.

‘When things happen overseas there’s this callout to condemn, and I think the Muslim community feel they have been condemning for the last 15 years… and young people especially feel like they shouldn’t be answerable or made accountable for things they have no control over,’ she said.

‘We’ve condemned enough.’

It’s a role that the ICV seems destined to repeat, and be largely confined to. Ms Chaudhry seemed resigned to it, labelling Islamophobia a ‘distraction’, while Mr Thomas was more optimistic, perhaps a result of being the new kid on the block.

‘There’s always been somebody,’ said Ms Chaudhry.

‘The “other” that we don’t have control over, but seems to define us at the same time.’

Ms Chaudhry reels off the list as she would her grocery requirements; ‘Osama bin-Laden and Al Qaeda, Hamas, Islamic State,’.

It’s a level of detachment that shows just how removed from groups like Islamic State ordinary Muslims in Australia feel, despite constantly being linked to them.

‘The issue is we don’t have media advocacy bodies,’ Mr Thomas said.

‘We tried to form a body… there’s a shortage of institutional power and resources; we’re limited to libel, slander. And that’s it.’

So how can the ICV go about disassociating Islam from terrorism when they are up against ‘institutional racism’? Aside from proactivity on both sides, there seems to be little chance of the cycle of condemning and in return being condemned from changing.

Ms Chaudhry said that Islamophobia has been developing over such a long period of time through political institutions, the work environment and the media that peoples minds and views had been directly shaped on ‘something they don’t fully understand.’

‘The stereotype makes us homogenous when we’re actually so diverse when it comes to cultural backgrounds.’

The key to the ICV’s plight, as is so often the case, appears to be awareness.

As Mr Thomas put it, ‘Islam is incredibly fluid, it’s very open to culture. It’s about tolerance.’

Therein lies the problem for the ICV: creating awareness in the face of established perceptions. You just hope that tolerance is a commodity which Australians will prove to be in steady supply of.

Ms Chaudhry still found cause for optimism.

‘My everyday interaction with people is goodwill,’ she said.

As I left down the stairs I was once again assaulted with the smell of iodised sterility. It seemed appropriate in an office that has devoted so many of its resources to cleaning up the mess created by a radical minority.

The ICV has worked to shake Islam free of any association with Islamic terrorism, and with the Western assault on IS-controlled Mosul expected to create further disorder in the Middle East, the council looks set for a long and difficult cleanup.

But they can’t act alone, the gap must be bridged on both sides if we are to ever to raise a level of awareness. Then, the cleanup can begin in earnest.